Is There Actually A Ninth Planet In Our Solar System? Here's What We Know

On August 24, 2006, our solar system lost a planet. It wasn't by cataclysmic destruction, but rather by the vote of the International Astronomical Union, which declared that Pluto, considered the solar system's ninth planet since its discovery in 1930, had been reclassified as a dwarf planet. Just like that, our sun's planetary community was reduced to a mere eight members, but that number might not actually be accurate.

10 years after Pluto lost its status as a planet, a paper appeared in The Astronomical Journal presenting evidence for an unseen object in the outer reaches of the solar system so large that it couldn't be anything but a planet. This paper was authored by California Institute of Technology researchers Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown, the latter of whom spearheaded the reclassification of Pluto.

Batygin and Brown formed their hypothesis after observing objects in the (perhaps surprisingly large) Kuiper Belt, a ring of small, icy bodies beyond Neptune that includes Pluto and other dwarf planets like Eris. They noticed a group of six Kuiper Belt objects that are clustered together, following unusual elliptical orbits that take them out of the solar system's plane, where the eight known planets reside. The odds of such an alignment being merely coincidental are around one in 15,000, according to the researchers, but something else could explain the phenomenon: a planet in the outer regions of the solar system, so large that its gravitational force is pulling on the other objects.

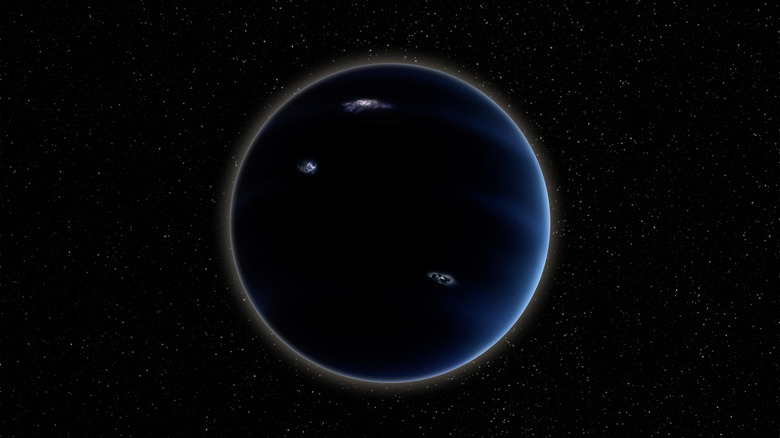

What scientists think a ninth planet could look like

In forming their Planet Nine hypothesis, Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown's research team ran computer simulations to determine the size, mass, and orbit of a planet required to explain the clustering of Kuiper Belt objects they had observed. They estimate that Planet Nine would be a gas giant of approximately the same size as Uranus and Neptune. However, the models indicate that Planet Nine is about five to 10 times more massive than Earth, while Uranus has the mass of 14.5 Earths and Neptune the mass of 17.1 Earths. This potentially means Planet Nine is the least massive of the gas planets.

The most remarkable thing about Batygin and Brown's proposed Planet Nine is where the models place its orbit. To explain the observed Kuiper Belt activity, Planet Nine would have to have an orbit between 20 and 30 times further from the sun than Neptune. This would mean that a year on Planet Nine would last between 10,000 and 20,000 Earth years. The planet's orbit would also have to be anti-aligned, meaning that its perihelion (the point when it is closest to the sun) is in the opposite direction of that of the other Kuiper Belt objects. While Batygin and Brown believe they have identified the planet's orbital range, they have no idea where it might currently fall in its orbit, and with such a long orbital period, narrowing it down won't be easy.

Planet Nine is a controversial subject in astronomy

Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown's study started a firestorm in the astronomical community. Many others picked up on the hunt, with more supporting evidence coming to light. One recent study suggests there's a 40% chance of Planet Nine existing, but it was likely ejected to the outermost reaches of the solar system in its nascent stages. However, there are also a great many skeptics of the Planet Nine theory, and they also have strong arguments in their favor.

Batygin and Brown's research isn't the first time that someone has proposed the existence of a very large planet beyond Neptune. That idea goes back even before the discovery of Pluto. Scientists had previously been baffled by irregularities in the orbit of Uranus, but they later found that these were merely the result of measurement errors, and it has left many in the astronomy community hesitant to jump to bold claims about Planet Nine when simpler answers may exist.

Already, holes have appeared in the Planet Nine theory, like the discovery of trans-Neptunian object Ammonite, whose orbital behavior seemingly goes against the existence of a ninth planet. Other recent discoveries within the Kuiper Belt pose the same problem. The claim will continue to stir controversy unless a ninth planet is actually observed, but that won't be easy. It would take over a century for a space probe to reach its theorized orbit, and even then, we have no idea where along that multi-thousand-year orbital path the planet could currently be.