When A Submarine Implodes, What Actually Happens?

Unless you have been living under a rock, you probably heard about the OceanGate submersible that attempted to dive to the Titanic in 2023 but never returned. What happened is way more brutal than most people realize. Everyone assumes submersible disasters involve water slowly flooding in, but with an implosion? Completely different ball game. To give you some context, we deal with about 15 PSI of pressure at sea level. Down where the Titan was going, which was almost 13,000 feet deep, it's well over 6,000 PSI.

While subs are made to handle intense amounts of pressure, they are also extremely precise. Even the slightest variation in manufacturing, the tiniest fiber layer that didn't bond right, a singular bolt that's been through one too many stress cycles – and it's pretty much game over. With the slightest leeway, water is going to flood the inside of a submersible at over 1,500 miles per hour. Which causes the air inside to compress so violently that it creates a massive explosion of heat and energy. The whole hull just caves in on itself — like crushing an empty can with your hand. As underwater robotics expert Michael Brannigan told Belfast News Letter at the time, "I'd probably say they didn't even see it coming."

How deep-sea pressure destroys a vessel

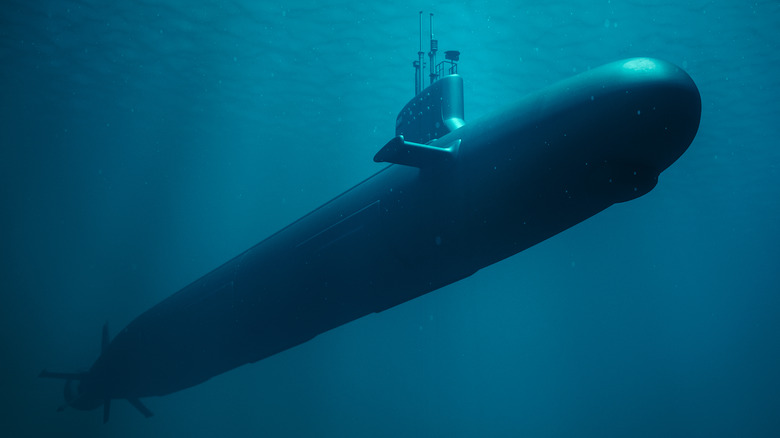

Vehicles like airplanes or spacecraft are designed to keep all that pressure in. But submersibles are fighting to keep it out. And that's a completely different challenge. Water doesn't give you any breaks (that's even true when it comes to this potentially disastrous leak at the bottom of the sea). It just keeps pushing from every direction, never letting up. Military subs deal with this by using heavy-duty steel or titanium, shaped into cylinders so the stress gets spread out evenly. They test these things constantly, inspect them for years, and upgrade them when needed. However, experimental deep-sea vessels are where things get risky.

Take carbon fiber, for example — some newer subs use it instead of the usual steel or titanium. While it is a lot lighter and can take a beating, carbon acts very differently from metal under extreme pressure. Metal will bend, dent, and show you warning signs before it fails. Carbon fiber doesn't give you that luxury. The real problem happens inside the material where you can't see it. Microscopic cracks start forming, and the layers begin separating — this is what engineers call delamination.

What history tells us about submarine implosions

The Titan disaster might have gotten all the attention, but actually, submarine implosions have been happening for decades. Not only that, but most of them could've been prevented. Back in 1963, the Navy lost the USS Thresher during a deep-dive test. A bad weld in one of the pipes caused flooding. Then the electrical system got fried, which knocked out the ballast system that could've saved them. The sub went past its crush depth and imploded. All 129 people died instantly.

Five years later, the USS Scorpion just vanished on its way back to Norfolk. They found it later with the hull split in half, way deeper than it was supposed to go. Nobody knows exactly what went wrong, but there are a number of different theories. Maybe the battery died, or maybe a torpedo malfunctioned — but everything points to the pressure finally winning.

What an implosion leaves behind

When a sub implodes, there's no wreckage like you'd see from a plane crash or a ship that goes down. What's left is a debris field of mangled metal, broken parts, and pieces that got shredded by forces way beyond what any hull could handle. The sub usually fails at its weakest spots — where different sections connect, joints between materials, that kind of thing. Structural parts get ripped off. The air inside gets compressed so fast that it creates these violent shock waves that push outwards while the walls are collapsing inwards. You may find a deformed titanium cap here or a twisted chunk of steel there, but rest assured, everything else is going to get annihilated and turn into debris. When they went looking for Titan, the pieces were scattered everywhere on the sea floor. The titanium front section was sitting by itself, completely separated. The back end was stuck in the sea floor. What remained of the carbon fiber hull was in fragments, all warped and split apart from the pressure.

It's the same pattern with other submarine disasters. The Thresher debris covered thousands of feet at the bottom of the ocean, while the Scorpion split into two. The Kursk's forward compartment was torn down to nothing, thanks to the extreme pressure and heat. Rarely do the recovery crews have hopes of finding anyone alive down there. They mostly just send robots down to go through the spoils, use sonar to locate the bigger pieces, and then try to match what they find with the original blueprints. After all, an implosion isn't something you escape. It's a physics problem with one outcome, and the ocean always shows its work.