New Fossil Discovery Might Prove That Two Different Extinct Human Species Coexisted

A recent discovery at Lake Turkana in Kenya has scientists thinking there may have been two ancestral human species — or hominins — coexisting together. Thanks to a patch of wet silt that was buried by a volcanic ash bed for over 1.5 million years, a shallow stretch of shore made up of hominin footprints was left undisturbed by the elements and ancient animals. Researchers have labeled this discovery region as layer TS-2, and human relatives aren't the only findings on this ancestral slab — the tracks of wading birds, bovid hoof marks, and impressions from horse-like animals were also found.

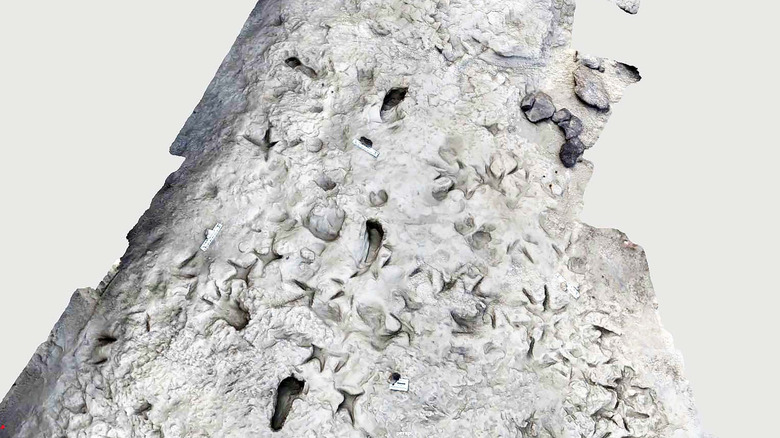

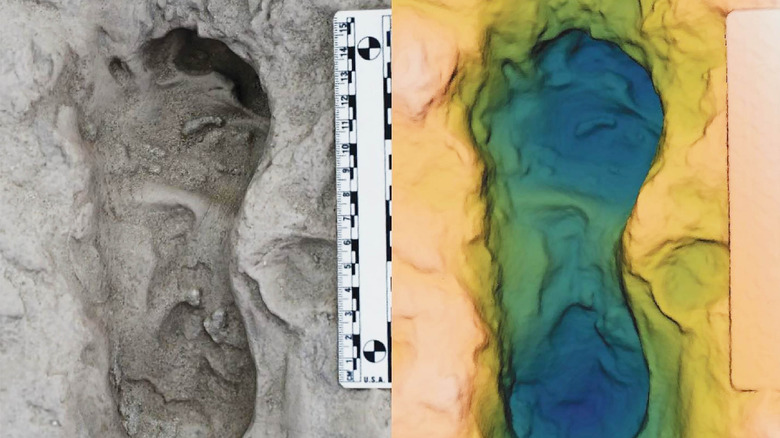

Regarding the hominin activity in the area, researchers were able to map one continuous footprint trackway from what experts believe was a single individual, as well as three separate hominin prints likely made by three other individuals. By way of three-dimensional computer analysis, researchers were able to map the prints of two extinct human species sharing the shoreline: Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei.

Because layers of fine sediment covered the ancient top layer in mere hours or days, the footprints were able to become trace fossils, a class of remains that includes things like footprints, burrows, nests, or coprolites (poop). Discussing the findings, Craig Feibel — a professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and Department of Anthropology at the Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences, and contributing author to the study published in the journal Science – remarked, "This proves beyond any question that not only one, but two different hominins were walking on the same surface, literally within hours of each other."

Footsteps at the water's edge

Feibel went on to say that, "The idea that they lived contemporaneously may not be a surprise. But this is the first time demonstrating it. I think that's really huge." The most unmistakable evidence that researchers were dealing with two distinct species came from the undeniable presence of two recurring gait patterns appearing side by side. The footprints also showed up on the same kinds of Pleistocene surfaces at regions of a similar age that were close to the Koobi Fora area, an anthropological hotbed for the study of prehistoric human activity.

The 3D model captures the footprints of H. erectus and P. boisei crossing at a near-perpendicular angle, an intersection frozen in time. Thanks to the fine detail preserved in these trace fossils, researchers can probe deeper into the region's anthropological story. Did these two species encounter one another at the lake's edge? If so, how did they navigate the possibility of conflict? Were resources shared or contested? Kevin Hatala, the study's lead author, offers further insight. "With these kinds of data, we can see how living individuals, millions of years ago, were moving around their environments and potentially interacting with each other, or even with other animals. That's something that we can't really get from bones or stone tools."

Walking into our past

While footprints alone can rarely identify a species, the repeated pairing of two distinct gait patterns across the region provides scientists with motion-driven evidence. Throw in the pre-established fossil record of the neighboring area — on top of volcanic layerings acting as preservation time stamps — and you've got yourself a locomotive snapshot of early hominin life.

This discovery also underscores how movement itself was a means for survival. Tools and a proper diet could only get you so far in ancient times, but efficient travel linked everything together. The ability to walk long distances meant better chances of finding water, food, and shelter. It also shaped encounters with neighboring species, sometimes forcing cooperation and sometimes sparking competition.

With each advance in technology and every new trace fossil unearthed, researchers continue to move closer to reconstructing a vivid portrait of early human life, back when survival was the only priority, and there were no smartphones to take pictures of you, your friends, and your foes (as far as we know).