9 Lightning Myths You Need To Stop Believing (And What's Actually True)

It starts with a flash that slices through the sky. Moments later, thunder follows with a deafening rumble. You are told to stay indoors, unplug your phone, or avoid touching anything metallic. Some warnings are rooted in science, but others are nothing more than myths passed down through generations.

Lightning is one of nature's fiercest forces. A single strike can carry over 300 million volts of electricity and reach temperatures hot enough to vaporize metals. This leaves no doubt that it can kill instantly or cause life-threatening injuries. In the United States alone, it kills 10-30 people each year and injures hundreds more. Worldwide, the toll is even higher, although many of these fatal or damaging incidents could have been prevented with accurate advice.

What makes lightning even more dangerous than its raw power is the false sense of security created by myths. Believing in the wrong thing at the wrong time can put you directly in harm's way. Let's break down the most common lightning myths and explain science-backed truths that could save your life.

Lightning never strikes the same place twice (Myth)

This old saying has a reassuring ring to it. Imagine standing near a tall tower during a thunderstorm, lightning flashes once, and someone tells you it's done for the day. It almost makes sense, as if the storm has moved on to find a new target. But this idea, while comforting, is simply not true, and believing it can be dangerous.

In reality, lightning doesn't track where it last struck. It strikes wherever the conditions are most favorable. In fact, the same spot can be hit dozens of times during a single storm. Tall, exposed structures made up of steel and concrete provide the easiest pathways for electricity to reach the ground. That's why skyscrapers, turbines, and lighthouses are struck so frequently. The Empire State Building in New York, for example, is struck around 20 to 25 times each year. During intense storms, it can be struck multiple times within minutes.

Critical structures are often designed with lightning protection systems built in, because repeat strikes are expected. Wind turbines, broadcast towers, and even airplanes rely on these systems to control lightning bolts. As long as the storm lasts and the conditions hold, lightning can strike the same place again.

Wearing jewelry attracts lightning (Myth)

For generations people have warned against wearing earrings, rings, or necklaces during a storm. On the surface, the logic seems sound — metals conduct electricity. But lightning isn't drawn to shiny accessories; it simply follows the laws of physics. What really guides a strike is height, isolation, and conductivity of the path to the ground. Someone holding a metal rod in an open field is far more at risk than someone walking down a busy street wearing bronze earrings.

This doesn't mean jewelry is harmless during a strike. While it won't lure a bolt from the sky, it can make the injuries more severe if you get struck by lightning. Metal conducts electricity efficiently, which means burns can be more concentrated and shocks more intense when jewelry is involved. The real danger isn't attraction, it's amplification.

That's why safety experts focus less on what you're wearing and more on where you are. Removing jewelry won't protect you from lightning, but moving indoors or into a fully enclosed vehicle will. The moment you hear thunder, you should find shelter rather than worry about your earrings.

If it's not raining, you're safe (Myth)

On what appears to be a perfectly clear day — the sun shining, the sky free of clouds, and the atmosphere seemingly calm — a bolt of lightning flashes across the sky, striking the ground nearby. This isn't science fiction but a rare dangerous event known as a bolt from the blue. It occurs when lightning travels sideways through the air from a storm that's up to 25 miles away before hitting the ground.

That's why waiting for raindrops as a signal to seek shelter is so misleading. People assume they're safe until the storm is directly overhead, but lightning often strikes before the rain arrives. Many victims are not caught in the middle of a storm at all; but on the storm's leading edge, where the skies still seemed calm.

Thunder is the warning sign, not rain. If you can hear it, you're already close enough to be struck. The next time a distant rumble interrupts a sunny afternoon, take it as nature's cue to head indoors.

Lying flat on the ground protects you (Myth)

At first, this myth sounds convincing. If lightning is attracted to tall objects, then lying flat on the ground should make you safe. But the reality is more complex. Lightning doesn't strike only the tallest object; it seeks out the most conductive path to the ground. And sometimes, that path is the ground itself.

When lightning strikes the earth, the electrical charge spreads out across the surface in what is called ground current. This phenomenon is far more dangerous than many realize, accounting for a significant number of lightning-related injuries and deaths. Lying flat only makes the risk worse by increasing the surface area of your body in contact with the electrified ground, allowing more current to flow through you.

So what should you do instead? Experts recommend crouching low, head tucked, and your hands covering your ears, minimizing your contact with the ground. While not a safety guarantee, this posture reduces your exposure compared to lying flat. Lightning isn't predictable but one thing is clear; during a thunderstorm, the ground isn't your ally.

Lightning only strikes during heavy rain (Myth)

Lightning doesn't need rainfall to strike. It is completely independent of precipitation. Yet the myth that lightning only comes with rain prevails, leaving many people with a false sense of security. If thunder rumbles but no rain falls, some assume they are safe. The fact is, lightning often strikes before the rain begins, and sometimes without any rain at all.

Research has shown that lightning can occur in conditions far beyond a typical thunderstorm. It has been recorded during snowstorms, dust storms, and even volcanic eruptions. You may wonder, what does a volcanic eruption have to do with lightning? But the principle is the same: intense atmospheric activity generates electricity, and when those charges discharge, lightning appears.

The crucial point is that a lack of rainfall does not stop lightning from striking. That's why the safest response to thunder, whether the sky is pouring or perfectly dry, is to move to proper shelter immediately.

Shelters like tents or sheds keep you safe (Myth)

It's a common misconception that tents or wooden sheds can protect you during a thunderstorm. The danger is that they offer no real safety. A tent, no matter how durable or water-resistant, is essentially fabric stretched over poles. Similarly, small sheds or cabins without proper wiring are little more than wooden boxes. Lightning seeks the fastest path to the ground, and because these structures aren't grounded, the electrical current can travel through them, striking anyone inside.

The good news is there are reliable alternatives. During thunderstorms, avoid open shelters, temporary coverings, or any structure without grounding. Instead, seek protection in a substantial building equipped with proper wiring and plumbing. These systems safely direct lightning into the earth. Vehicles with their windows closed are also effective, acting as a protective shell that channels electricity around you rather than through you.

If you're ever caught outdoors with no proper shelter nearby, the safest option is to minimize your risk until you can move. Stay away from tall, isolated objects like trees or poles, avoid open fields and hilltops, and keep clear of water, which is highly conductive.

You can't be struck indoors (Myth)

It's a mistake to assume that simply being indoors makes you completely safe during a thunderstorm. When lightning strikes a building, it seeks the most conductive pathway to the ground, often traveling through plumbing, electrical wiring, or even metal frames. This means everyday objects inside your home can unexpectedly become dangerous.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one-third of lightning injuries occur indoors, most often during the peak of summer storms. Touching anything connected to a power source, like a corded phone, a plugged-in mobile phone, or even a game console, can make you the conductor lightning is looking for. Many people find it hard to believe, but these items can serve as direct channels for electrical energy, even if there's no power in the building.

Water carries the same risk. Taking a shower, washing dishes, or even doing laundry during a thunderstorm can expose you to lightning traveling through plumbing systems. So while being indoors is far safer than being outside, it's not an absolute shield. Your safety also depends on what you avoid touching or doing until the storm passes.

Lightning victims are electrified and can shock you (Myth)

This myth must be debunked because it can cost lives. A person struck by lightning does not carry any residual electric charge afterward. The idea that touching them could shock you is completely false. It's safe to make contact, and in fact, immediate help is critical. Many lightning fatalities occur because the strike triggers cardiac arrest or respiratory failure. Quick intervention, especially CPR, can mean the difference between life and death.

Survivors may suffer lasting effects such as brain injuries, internal burns, insomnia, or neurological complications. This makes both awareness and rapid response essential. It's best to prioritize victims who appear lifeless over those who are moving, because the lifeless victims are often in cardiac arrest and may be revived with immediate care. Treat them as you would anyone in a medical crisis; step in quickly, provide aid, and call emergency services.

It's also important to distinguish lightning strikes from other forms of electrocution. Victims in contact with live electrical sources, such as power lines or faulty wiring, can be dangerous to touch until the current is cut off. With lightning, the danger passes instantly; with man-made electricity, it may persist.

If you're not the tallest object, you're safe (Myth)

Height does play a role in attracting lightning, but it is not the only factor. Lightning also responds to conductivity, distance, and even moisture in the environment. In some cases, it can travel for miles through the air and strike objects that aren't the tallest in the area. This happens because lightning ultimately follows the path of least resistance, not simply the highest point.

This makes trees especially dangerous during storms. People often assume that standing under a tall tree provides protection, but it really does the opposite. Trees are filled with moisture, making them excellent conductors. When lightning strikes a tree, the electrical current can travel down the trunk and explode outward into the ground, or even jump to anyone sheltering under it. In such cases, the victim can be injured by both splintered wood and ground current.

The safest move is never to rely on trees or tall objects as shields. Instead, seek proper shelter in a fully enclosed building or vehicle, where wiring and metal structures safely direct the energy into the ground.

Lightning and water are a deadly combo (Truth)

Here's something everyone should know: think twice before showering, swimming, or boating during a thunderstorm. Lightning and water are a dangerous combination. A common misconception is that lightning must strike a person directly to cause harm, when actually lightning only needs to hit the water nearby to make you part of its deadly circuit.

When lightning strikes a lake, river, or ocean, the electrical energy doesn't stay in one spot. Instead, it spreads out rapidly across the surface and just below, creating a wide zone of electric danger. Anyone in or near that water is at serious risk of electrocution, even if the bolt struck far away. The same principle applies to indoor plumbing. Showering or using running water during a storm can expose you to electricity traveling through pipes.

That's why lightning incidents involving swimmers and boaters often end in tragedy. The science is that water conducts electricity, and the human body is about 60% water giving lightning an easy path. So if a storm approaches, the safest move is to get out of the water and stay far away. If you're wet, dry yourself quickly because wet skin increases conductivity and makes you more vulnerable to lightning.

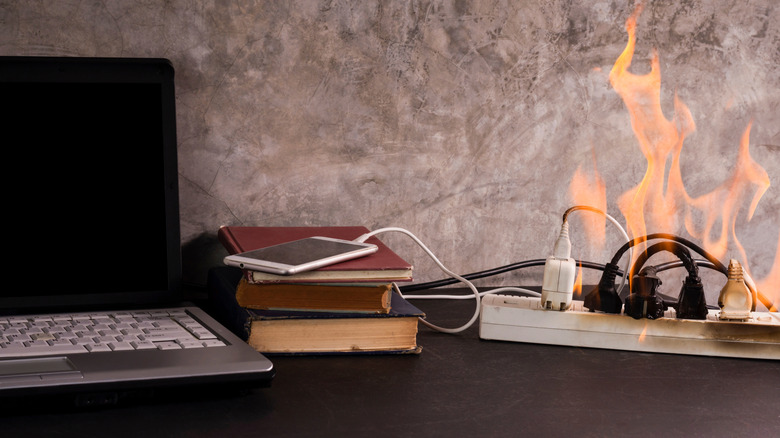

Avoid using plugged in electronics during a thunderstorm (Truth)

It may be inconvenient, but one of the safest choices you can make during a thunderstorm is to stop using plugged-in devices. Lightning can enter the electric circuit through powerlines, sending a massive surge through your home's wiring, even if the power is out. That surge can destroy electronics and, in some cases, injure the person using them.

Many people assume surge protectors will shield their devices, but lightning is far stronger than those defenses. With hundreds of millions of volts, a strike can easily overwhelm even heavy-duty protectors, leaving your appliances and gadgets exposed. In comparison, the typical household voltage is only 120 volts in the United States.

The best protection is prevention. Unplug sensitive electronics before a storm arrives, and avoid using your washing machine, dishwasher, or corded devices while lightning is active in your area. Waiting until the storm passes is a far safer option than relying on equipment that simply can't match the raw power of a lightning strike.

A closed car is a safe shelter (Truth)

A car with a metal roof can provide excellent protection during a thunderstorm — but only if the doors and windows are fully closed. The reason lies in physics: the vehicle acts as a Faraday Cage, an enclosure of conductive material that shields whatever is inside from external electric fields.

This protection works because when lightning strikes the car, the metal body redirects the electrical current around the exterior rather than letting it pass inside. Another principle at play is the skin effect, which means electric current flows along the outer surface of a conductor. In practice, the lightning's energy travels around the car's body and safely into the ground, leaving the inside largely unaffected.

It's worth noting that not all vehicles offer this protection. Convertibles, motorcycles, bicycles, and cars with fiberglass or plastic shells do not provide a continuous conductive surface, so they cannot act as a Faraday Cage. For maximum safety, you need a fully enclosed, metal-roofed vehicle with the windows and doors shut. While inside, avoid touching exposed metal parts.