Scientists Had Moss Grow On The Outside Of The ISS For Months - Here's What Happened

Researchers recently mounted moss spores on the exterior of the International Space Station during the Tanpopo 4 mission for 283 days (roughly nine months). The goal was to figure out if Earth-based life could survive the harsh ravages of space, and the survival of "Physcomitrium patens" suggests that it certainly can.

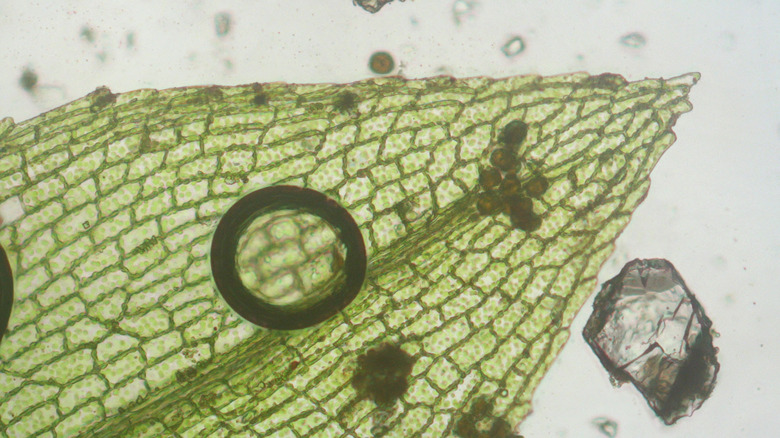

Moss goes through several changes in its life cycle, but the researchers specifically chose moss still encased in their sporophyte structures, since they were the most resilient in this stage. These encapsulated spores were as much as 1,000 times more resistant to UV radiation than the moss' brood cells. In lab simulations, the spores maintained an 80% germination rate after 30 days at -80 degrees Celsius (-112 degrees Fahrenheit), and a 36% rate after 30 days at 55 degrees Celsius (131 degrees Fahrenheit).

The sporophyte's outer cell layers act as a protective barrier against drying out, radiation, and temperature extremes. Mosses are known to be among the earliest terrestrial plants, but leaving a water-rich environment to come onto land means adapting to the lack of ready water. This adaptation showcases evolution that helped bryophytes colonize land environments.

The little moss that could

After a nine-month stint attached to the exterior of the ISS, the moss spores showed an 86% germination rate (compared to 97% for the control moss kept on Earth). These results demonstrated how resilient the moss was, coping with the most extreme conditions in space.

Among all the things that could damage the moss, researchers highlighted UV radiation as the most significant threat. Surprisingly, extremes in temperature and the vacuum of space had little effect on germination rates. However, UV radiation caused an 11% drop compared to the control specimens. All samples, whether exposed to UV or not, showed roughly 20% chlorophyll degradation.

Even samples protected by UV filters showed similar degradation, suggesting that it was space's intense visible and infrared light (unfiltered by any atmosphere) to blame. The findings highlight how photosensitive these plants are in non-terrestrial environments. Additionally, this experiment marks the first time scientists have confirmed bryophyte survival after actual space exposure and Earth return.

Space agriculture may be possible

Using the nine-month window and extrapolating, researchers developed a model that suggests the moss could survive for around 5,600 days in space, but this model has its own flaws. It's based on just two data points (pre-exposure and nine-months post-exposure), meaning that much more research needs to be done before they can have a realistic estimate.

The findings have practical implications for potential Moon and Mars missions. Mosses are "pioneer" species, meaning they're the early organisms that help to develop the soil for later, more complex lifeforms, like how peat moss operates back on Earth. Scientists have highlighted bryophytes like these as good candidates for bio-regenerative life support systems on space stations or planetary bases. Mosses offer a lot of benefits over traditional crops or other simple plants like algae. Their ability to survive and even thrive in low-light environments makes them ideal for space stations or colonies situated far from the sun. Their ability to produce oxygen while fixing carbon dioxide deals with two environmental concerns at the same time.

The experiment moves space agriculture from just another theory to something we may actually see happen. Addressing food security off-planet, one of the most important failure points in long-term space settlement, just became a little more realistic.