How Did Mars Get Its Moons?

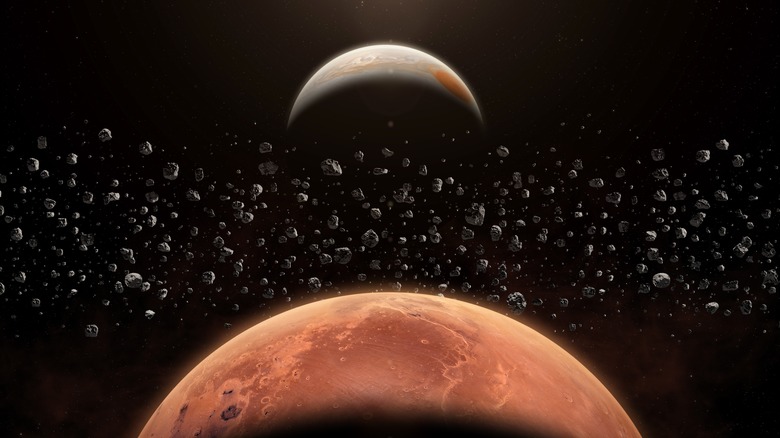

Six planets in the solar system have at least one moon. Both Earth and Mars are toward the lower end of the lunar count, as our home planet only has one moon, and Mars has two. But not all moons share the same origin story, and some experts believe that the lunar bodies of Mars — Phobos and Deimos — weren't actually "formed," but "captured."

We can elaborate further by comparing the formation of Earth's single satellite to Mars' lunar duo: One of the leading theories is that roughly 4.5 billion years ago, a massive protoplanet (think of this as a full planet in the making), referred to as Theia, collided with an earlier version of Earth. The impact likely sent all kinds of planetary debris into orbit, and after time and gravity took their toll, some of this cosmic detritus was bonded together to form the moon.

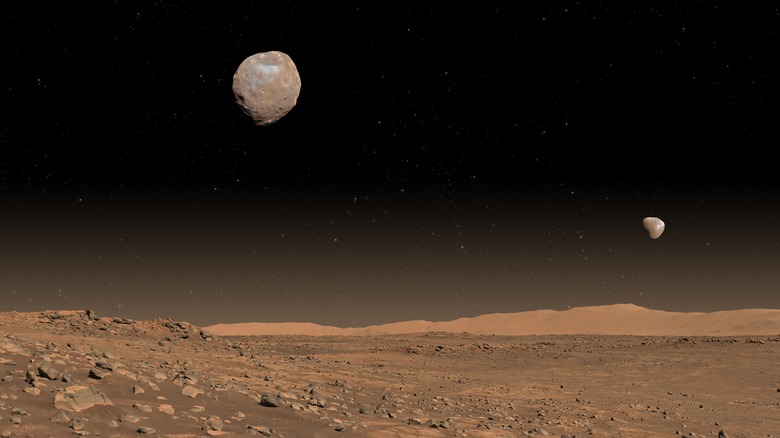

The moons of Mars are quite different than Earth's, though, even by appearance: Both Phobos and Deimos are far smaller than Earth's single moon, are riddled with craters, and have a dark, icy, carbon-rich composition — some of the key calling cards of an asteroid. This has led some scientists to theorize that Mars' gravity pulled in asteroids from a neighboring belt, and the two that remained in orbit came to be known as Mars' two satellites.

That's not only the theory on the formation of Mars' two moons

How Phobos and Deimos came to be is still up for debate, and another popular hypothesis has more in common with how Earth's moon eventually showed up: Scientists theorize that in the early days of our solar system, a massive cosmic structure may have collided with Mars, sending planetary debris into orbit. Add a lot of time and gravity, and many moons later (pun intended), Phobos and Deimos were formed.

There's also a new theory that sort of combines the two leading theories as to how Phobos and Deimos showed up: According to supercomputer simulations carried out by a research team led by Jacob Kegerreis, a postdoctoral research scientist working with NASA, an asteroid passing by Mars could have been sucked up and torn to bits by the planet's intense gravity.

Some of these fragments escaped Mars' gravitational pull, while others remained in orbit. These orbiting fragments continued to collide with each other, getting smaller and smaller. Through the years, these cosmic bits coalesced to form Phobos and Deimos.

We might get some answers soon

Our best shot at cracking the code on how Phobos and Deimos came to be lies with the upcoming Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission. Headed by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), researchers plan to send a spacecraft into orbit around Mars, with planned visits to both Phobos and Deimos. The vessel is also supposed to land on Phobos' surface to gather a geological sample to bring back to Earth for further analysis. As of October 2025, the MMX is on track to launch sometime in 2026, with a planned Martian orbit insertion by 2027, and a return to Earth by 2031.

Fingers are crossed that whatever samples the MMX lander is able to gather may give us some revelatory info on Phobos' composition: Is it made up of clay and silicate like an ancient asteroid, or are we dealing with an iron-rich satellite chunk ejected from Mars a long, long time ago (in our galaxy, but still far away)?

In the meantime, we Earthlings still have telescopes, orbital facts, and computer models to aid our Martian moons speculations, but remote observation can only get us so far. This is why the MMX mission's success is so critical — with that lunar sample, we finally have a chance of pulling back the curtain on where Phobos and Deimos came from.