Every Physical Object Breaks The Same — Even Bubbles

Randomization and chaos exist throughout the known universe. Yet, while the state of all things does fundamentally devolve to pure chance, scientists have constantly researched the variables governing these chances and worked on figuring out rules and optimal algorithms that can describe them. Even something that seems like it can't be described by one set formula, like the number of fragments produced by breaking something, has factors that let you calculate an answer.

What makes this even more interesting is that this answer applies to all sorts of materials, not just those similar to one another; whether it's a solid mirror being dropped on the ground or a bubble bursting mid-air, the relationship between the number of smaller fragments and bigger ones follows a strict power law. Granted, figuring out how things break might not seem as big of a victory for science as bringing back an extinct bird, but this finding has potential to be applied to natural disasters, the cosmos, and even human society.

Emmanuel Villermaux from the University of Aix-Marseille proved this last November in a paper approaching the problem of fragmentation through a different lens. While most people tried looking at the specifics through a microscope — thinking that the number of fragments relates to the specific micro-materials making up the object — Villermaux instead focused on the global kinematics affecting the object. Regardless of the material or the force used, the force itself geometrically divides any space in the same way; the magnitude of force can affect the number of fragments and the size itself, but it cannot change the shape being divided into.

What is a power law?

In a normal distribution, you can find the average being the highest frequency. This will also follow a standard deviation, which means you can expect values around this average, but not too far away from it. An example of this is human height; the average height is one that you'd find the most people with, and while you can find people around this height — you won't have trouble finding people who are 5'1" or 6'5" — it's impossible to find someone that's 20 feet tall or shorter than 12 inches.

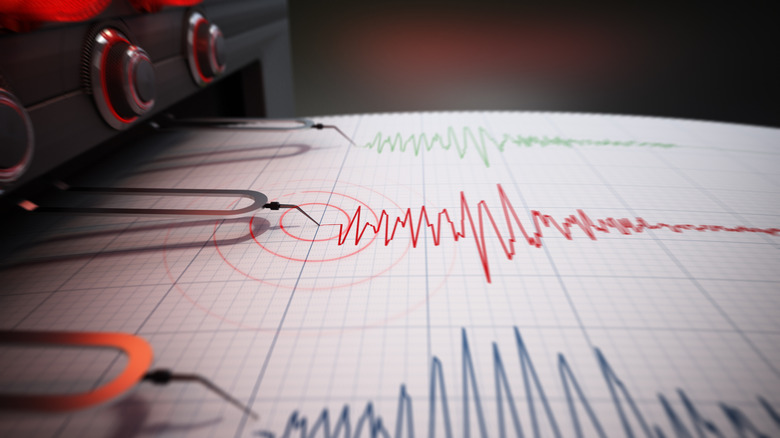

This is where a power law differs: In a power law, there are no strict limits on the magnitude, and the average isn't the most frequent. If we were to graph events resulting in large-scale deaths — earthquakes, tsunamis, or nuclear disasters – with their frequency and the magnitude of destruction, we wouldn't find a normal distribution. There are many smaller, relatively weaker ones, and then there are a few that were immensely destructive. Yet, if we were to average them out, the most common scale of destruction would not be the average. This is because the magnitudes of the larger ones aren't limited by standard laws of deviation, so their sheer size skews the results.

Villermaux proves that any fracture, regardless of size, material, or external circumstances, follows a power law in the number of differently scaled fragments produced. Put simply, the number of smaller fragments increases proportionally to the size of the larger fragments, and there are always more smaller ones than there are bigger chunks. With this, it's possible to figure out exactly how many small, medium, and large fragments there would be if you apply a certain amount of force, so long as the force being applied is known.

What makes this important?

Power laws govern most of our world. The laws of physics are really good at math, so even seemingly completely unrelated things often follow the same rules. Earthquakes, nuclear radiation, or how a disease spreads, these are all things which can be described by some sort of power law. As such, Villermaux's findings on the mechanisms of fragmentation and how things break can lead to making better predictions of critical areas in an earthquake or figuring out ways to contain a pandemic.

Since the discovery of power laws, there have also been ideas on applying them to social sciences. As these laws can be found in seemingly completely disconnected things, just like how there doesn't have to be any commonality between the different substance types during fragmentation, future developments will potentially be using the same method in working out how societal groups fragment and other similar trends.

While this power law applies to almost all objects, both liquid and solid, there are certain exceptions. For instance, certain continuous, free-flowing liquids — such as water flowing directly from a tap — as well as some types of plastics don't fully obey the rule.